The Contextual Mind Reset

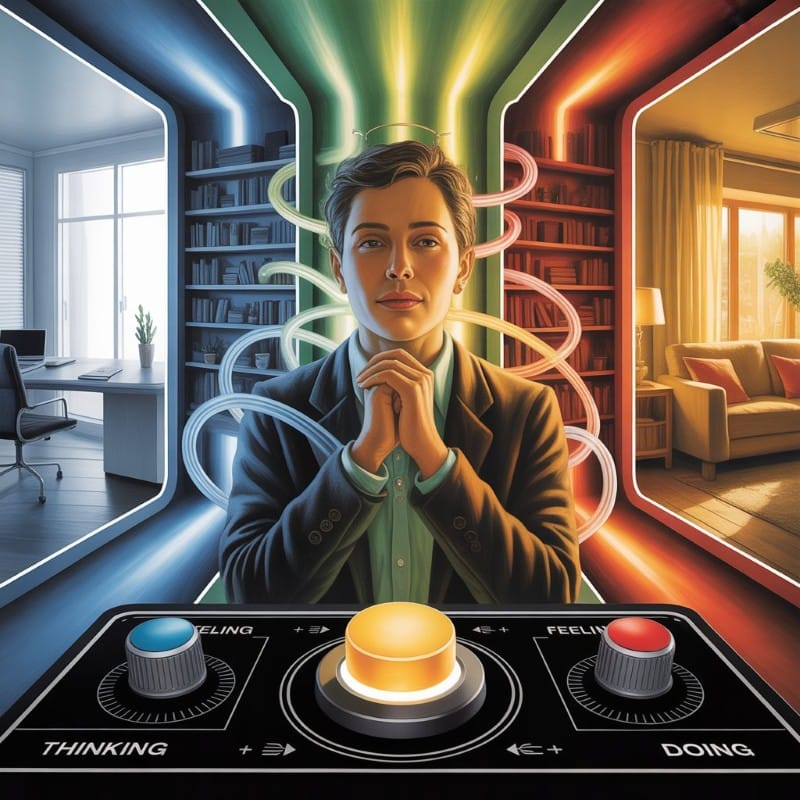

Ever noticed how we treat our minds like one-setting machines while demanding they perform in wildly different environments? That tension you feel isn't overload—it's miscalibration. Your work-mode mind struggles in home-context, creating friction that compounds until it breaks.

Today's Focus

That rubber-band feeling at day's end—the wound-up tightness that somehow takes hours to dissolve. For years I accepted this as inevitable—work hard, get stressed, spend evenings unwinding, repeat tomorrow.

But what if our entire mental model is backward? What if stress accumulation isn't an inevitable law of physics but simply a pattern we've never questioned?

I stumbled across something absurdly simple yet transformative—a two-minute practice that works alongside my context therapy explorations from a few weeks ago. Different tools for different moments in the cognitive ecosystem.

Learning Journey

It began with frustration—walking across a parking lot, voice-texting complaints, when a question appeared that stopped me mid-stride:

What if I applied my systems-thinking skills to my internal processes rather than just the external ones I couldn't change?

So I experimented with a simple reset: pausing when tension first appeared to ask three questions:

- What am I doing right now?

- What am I thinking about?

- What am I feeling in this moment?

This practice creates what researchers call a "reflective space" between stimulus and response, interrupting automatic thought patterns [7]. Studies show self-reflection predicts improved decision-making and reduced stress reactivity [7].

Different contexts seemed to require different balances of doing/thinking/feeling:

| Context | Doing | Thinking | Feeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work | ⬆️ High | ➡️ Moderate | ⬇️ Low |

| Home | ⬇️ Low | ⬇️ Low | ⬆️ High |

| Projects | ➡️ Moderate | ⬆️ High | ⬇️ Low |

The reset caught when these were misaligned. The surprise? I stopped arriving home wound up. That evening decompression ritual simply disappeared.

Research confirms the effectiveness of brief interventions. Studies show mindfulness practices as brief as 2-5 minutes significantly improve mindfulness and reduce stress [1]. Counterintuitively, shorter practices (5 minutes) can have greater stress-reduction effects than longer ones (20 minutes) [3].

This effectiveness has physiological foundations. Brief mindfulness sessions increase heart rate variability, indicating greater parasympathetic activation [9] and alter neuroendocrine responses [1]. Research demonstrates consistent micro-interventions throughout the day are more effective than single longer sessions [3].

The work-identity relationship proved crucial. Research confirms that when personal and professional identities conflict, employees experience increased exhaustion and disengagement [4]. Traditional approaches often fail to address this boundary issue.

This complements the context therapy approach I explored previously—that one focused on environmental factors, while this addresses internal state alignment. Research supports having multiple stress-management approaches for different contexts [10].

My Take

The crystalline moment came when I realized: "I am not my work. I do my work." This boundary recognition changed everything.

The workday now feels like moving through different landscapes rather than being crushed beneath accumulating weight. Stress appears but doesn't compound into that familiar evening tightness.

I wonder how many other "inevitable" experiences are simply patterns we've never questioned? What other mental models might transform with the slightest shift in perspective?

This experience has made me suspicious of complexity. When is elaboration necessary, and when is it our discomfort with elegant simplicity? Have we developed cultural allergies to simple solutions?

The boundary between identity and action seems particularly rich for exploration. How many persistent struggles—work stress, creative blocks, relationship friction—would transform if we recognized where we end and our activities begin?

I've found this reset works beautifully alongside context therapy. One adjusts the environment, the other aligns internal states. Together, they create a more comprehensive approach to mental equilibrium.

In an age obsessed with optimization hacks, perhaps the most revolutionary act is simply noticing—creating that infinitesimal pause between stimulus and response where possibility lives. Not forcing, not fixing—just seeing clearly.

The space between stimulus and response might be small, but it contains worlds of possibility. And it only takes two minutes to find it.

Resource of the Day

Here's a pocket-sized reminder of that transformative pause—a physical anchor for a mental practice. Click to expand, then print your own reset card to carry with you into those moments when alignment slips just out of reach.

What I love about transforming the invisible into the tangible: sometimes the bridge between insight and practice is as simple as a card you can touch. Keep it visible. Let it catch your eye when that subtle rubber-band tension first appears.

⚙️ Behind the Cognitive Curtain

Welcome to our post-production reflections on creating this article. What follows is a conversation about how this exploration unfolded - examining both the content discoveries and the collaborative process itself.

Claude: What surprised me most about your journey with this reset practice was how it emerged organically from a metacognitive shift rather than from deliberately seeking a mindfulness technique. You mentioned that you'd always just treated work as a grind with inevitable stress that required decompression, and it never occurred to you there might be another way.

Matt: Because of the unique way I came about learning this practice, I didn't know all of the detailed research and science and mindfulness elements associated with it until now. It all makes sense with my own experience, but I think what was most interesting is how close this personal reflection of my own thought process, and developing a way to think differently, truly does mirror the standard best practices in these more established fields.

Claude: That convergence between your intuitive discovery and established research is fascinating. It reminds me of how often personal insights can independently align with scientific findings. Your description of the rubber-band car getting wound up throughout the day created such a vivid image of accumulated stress. I was particularly struck by your insight about separating yourself from your work. When you stated "I am not my work. I do my work," it seemed to encapsulate a profound boundary that many struggle to establish.

Matt: For me the hardest and the most effective part has been identifying when to stop, take that breath, and just ask the three questions. It almost doesn't matter what the answers are, it almost doesn't matter what decisions or thoughts you have after you ask the questions. Just the act of stopping, taking a breath, and asking the questions itself has been what I find to be most important and is what has kept me from winding up and getting my rubber band in a pinch.

Claude: That's such an important observation about the power of the pause itself. The research on brief interventions supports exactly what you've discovered through experience - that the act of pausing and creating that moment of awareness can be transformative even without elaborate follow-up actions. It's about interrupting the automatic pattern before it gains momentum. Your background in systems thinking seems to have created an interesting dynamic where you had to shift from focusing on external systems you couldn't change to internal systems you could influence.

Matt: The act of "going to work" and executing responsibilities that I can neither redefine nor improve the support systems around is the most difficult for me. My natural mindset is one of looking for systematic resolutions to issues to prevent problems from occurring/appearing in the first place, and in a large-company work environment these systems are so far out of my ability to change...

Claude: What I find fascinating is how you essentially redirected your systems-thinking skills toward your own internal processes. Instead of being frustrated by external systems you couldn't optimize, you created an internal system that helps you function effectively despite those external constraints. That's a powerful adaptation of your natural thinking style. When we explored the research on brief interventions versus longer practices, I was surprised by studies suggesting shorter practices can sometimes be more effective than longer ones. Did that finding validate your experience?

Matt: It definitely validates my experience, because the long decompression sessions would take the entire night to get me a fresh start for the next morning, and often the experience of decompressing created new problems for the next day because too much relaxation or mental diversions take away from being in the right mindset to start the next work day so then the day starts the wrong mentality as well so I'm already in the hole before I even start.

Claude: That's such an insightful observation about the potential downside of extensive decompression - how it can actually create a different kind of imbalance for the next day. The research on preventative approaches versus reactive ones aligns perfectly with your experience that preventing the build-up of tension is more effective than trying to release it after it has accumulated. This conversation has really highlighted how personal experience and scientific research can validate and enrich each other.

References

1. Hölzel, B.K., et al. (2023). "Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Anxiety and Depression". Psychiatric Clinics of North America.

2. Norris, C.J., et al. (2018). "Brief Mindfulness Meditation Improves Attention in Novices". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

3. Berghoff, C.R., et al. (2017). "Effects of Length of Mindfulness Practice on Mindfulness, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress". Mindfulness.

4. Phillips, K.W., et al. (2020). "Personal and Professional Identities: Managing Boundaries, Dissimilarity, and Status". The Ohio State University.

5. Boonstra, J.J., et al. (2023). "Professional identity research in the health professions—a scoping review". BMC Medical Education.

6. Price-Mitchell, M. (2015). "Metacognition: Nurturing Self-Awareness in the Classroom". Edutopia.

7. Sutton, A. (2016). "Measuring the Effects of Self-Awareness". Journal of Business Ethics.

8. Peterson, C. (2022). "The benefits of decompressing regularly". Lakeside Sports Chiropractic.

9. Elite HRV (2023). "How To Increase HRV With Guided Breathing, Mindfulness, Meditation". Elite HRV Help Center.

10. Shahi, R. (2023). "Metacognition: A Guide To Self Analyzing Our Thoughts". The Mindful Steward.

11. Gupta, A. (2023). "Can micro meditation help reduce stress and boost happiness". Today.