The Social Skin of Everyday Objects

Ever felt weirdly naked without your hat? Picture your brain drawing invisible walls: private-you inside, public-you outside, hat as the doorway between worlds. That strange 'missing' sensation reveals how ordinary objects become powerful psychological border guards.

Today's Focus

So there I was, sitting in jury duty, feeling weirdly exposed. Not because of the courtroom drama or being surrounded by strangers. My head felt naked. Actually naked. Like there was this phantom pressure around my skull where my trusty ball cap should've been.

The sensation wasn't subtle either. It felt urgent, pressing - as if my brain was sending emergency signals: "Hey! Something important is missing up here!" And this wasn't about some fancy designer accessory I'd invested my identity in. Just a basic ball cap I'd been wearing for years without much thought.

Why would my brain create such a strong physical response to the absence of something that isn't even part of my body? It's a hat, not a hand!

Learning Journey

I started digging into this weird sensation and stumbled across this concept called "extended body schema" – this fascinating idea that our brains actually incorporate regularly used objects into our neurological self-image [1]. Like, my brain had literally redrawn its map of my body to include my hat.

That's wild, right? Our brains don't really respect the boundaries of our skin at all. They're constantly expanding outward, adopting tools and objects we use regularly as if they were actual body parts.

Musicians show this effect in really dramatic ways. Their instruments become neurological extensions of themselves after years of practice [2]. The brain literally creates new neural pathways that include these external objects in its mapping of the body. My casual ball cap habit had somehow triggered the same process as a concert pianist's relationship with their grand piano!

But wait—something didn't quite fit.

I only felt that "naked head" sensation in specific contexts. At home without the hat? Totally fine. Getting into my car to leave for jury duty? Suddenly my head felt as wrong as if I'd forgotten pants. The contextual nature of this feeling pointed toward something beyond just physical habituation.

This sent me down a rabbit hole into research on context-dependent rituals. Anthropologists talk about this thing called our "social skin" – the boundary layer we create between our private and public selves [3]. My cap had apparently become part of this boundary, a component of how I prep myself for navigating the outside world.

What's fascinating is how this connects to "transition rituals" – these ways humans mark shifts between different states or contexts [4]. These exist across cultures, from elaborate ceremonies to tiny personal habits. Getting dressed to leave the house is actually a mini-ritual that marks the transition from private to public life [5]. My cap had become part of my personal crossing-the-threshold ritual, similar to putting on "outside clothes" or a work uniform.

When I actually traced when this habit began, I realized something I hadn't connected before—it started during the COVID pandemic. What began as an occasional practical solution (bad hair days, sunny weather) transformed during 2020 when I discovered the cap could help lift mask straps away from my ears. That practical pandemic adaptation eventually morphed into this everyday habit that now feels weird to be without.

This evolution fits perfectly with research from this landmark 2009 study that found new behaviors take anywhere from 18 to 254 days to become automatic habits, with an average around 66 days [6]. Different habits form at different rates - simple behaviors become automatic faster than complex ones, and consistency matters most [7]. The pandemic definitely provided plenty of time for new routines to become deeply ingrained.

My Take

What started as a simple hat has transformed into something weirdly meaningful – a boundary marker between my private and public selves. I never actually thought about when or why I started wearing a hat regularly until this exploration. Tracing it back to the pandemic revealed something I hadn't considered: going out during that time required a kind of "armor," and the hat became a piece of that protective gear.

The connection to the public versus private self feels surprisingly true. Even now, post-pandemic, my hat signals a transition – when I go out, I "look" a particular way that's different from how I appear at home. It's not about fashion or signaling identity to others as much as it is about my own mental shift between worlds.

What shocked me most about this whole exploration was discovering how much psychology lies behind what I thought was just a simple physical habit. What I expected to be a straightforward discussion about "ghost sensations" of missing clothing opened up much deeper insights about ritual behaviors and transition markers.

Makes me wonder how many other supposedly simple habits might actually be serving important psychological functions in our lives – these little anchors and signals that help us navigate our complex social worlds without us even realizing it?

What small transition rituals have you developed without noticing?

Resource of the Day

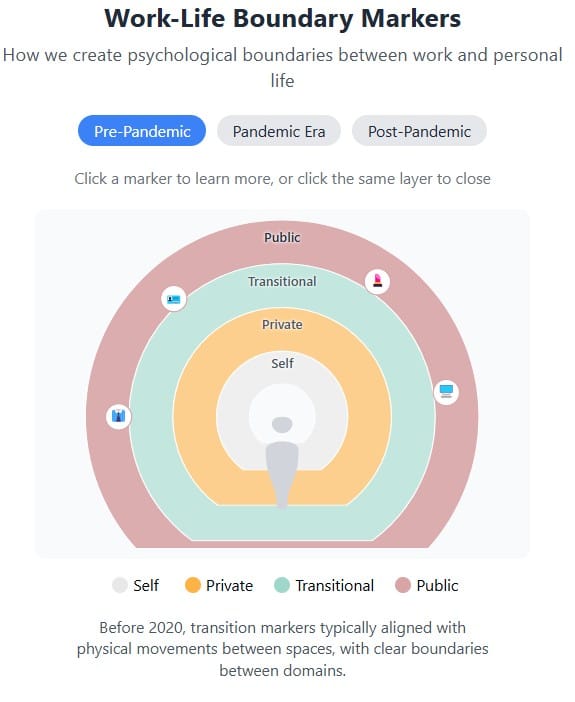

Explore how we create invisible boundaries between our work and personal lives with this interactive visualizationClick to explore the visualization.

By clicking through different layers—from our inner self to our public presence—you can discover the physical, digital, and psychological markers that help us transition between different parts of our lives. See how these boundaries evolved from pre-pandemic routines through the disruptions of lockdowns to our current hybrid approaches.

⚙️ Behind the Cognitive Curtain

Here's a peek into our conversation while exploring this weird psychology of everyday habits.

Claude: Your description of that "pressing" sensation around your skull without your cap is fascinating. It suggests your brain has literally mapped the cap into its body schema. I was struck by how you compared it to being without pants – that's such a powerful way to describe the feeling!

Matt: It's absolutely situation specific. I don't feel it inside the house. Not at all. But when I was getting in the car and starting to drive I felt an absolute sense of missing something. Especially that first day when it was probably the first time I'd left the house in years without wearing a cap.

Claude: That contextual element completely shifted our exploration! When you mentioned it only happened when leaving the house, it opened up this whole avenue about transition rituals and markers between private and public spaces.

Matt: I don't think it's any more special than putting on clothes that I'd wear in public or putting on a uniform to go to work, but I think it's deeply tied to both of those phenomenon.

Claude: That comparison was super illuminating! It connected your personal experience to these broader anthropological concepts about "social skin" and transition markers. I wouldn't have made that connection without your insight about uniforms and public clothes.

Matt: Before this conversation, I didn't ever really think about when I started wearing a hat regularly. I found it interesting to really connect to the origin of a habit and then to see how that habit becomes a behavior that transitions into something even more meaningful.

Claude: The pandemic connection was particularly revealing - how something that started as a practical solution for mask-wearing evolved into a psychological marker. It showed how rapidly objects can become integrated into our sense of self, especially during periods of significant adaptation like COVID.

Matt: It seems as if going out required armor and a hat was just a piece of that armor, that I built it as a way to have some sense of other-self when I'd go out. Now it's just a continuation of that, that when I go out I "look" a particular way different than at home, even if it's as simple as a cap.

References

1. Maravita, A., & Iriki, A. (2004). "Tools for the body (schema)". Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(2), 79-86.

2. Lotze, M., Scheler, G., Tan, H.R., Braun, C., & Birbaumer, N. (2003). "The musician's brain: Functional imaging of amateurs and professionals during performance and imagery". NeuroImage, 20(3), 1817-1829.

3. Turner, T. (2012). "The social skin". HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 2(2), 486-504.

4. Van Gennep, A. (1960). "The Rites of Passage". University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1909).

5. Kim, J., & Jang, H. (2017). "An Exploratory Study on Daily Grooming Ritual: Transition from Private Self to Public Self". ResearchGate.

6. Lally, P., van Jaarsveld, C.H.M., Potts, H.W.W., & Wardle, J. (2010). "How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world". European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 998-1009.

7. Gardner, B., Lally, P., & Wardle, J. (2012). "Making health habitual: the psychology of 'habit-formation' and general practice". British Journal of General Practice, 62(605), 664-666.