Why Can't We Find Addresses With The Radio On?

That instinctive reach for the volume knob when searching for an address? Your brain's running out of RAM. Closing unnecessary tabs—music processing down, visual navigation up—cognitive efficiency in silent action.

Today's Focus

Today's topic really hits me so often in my life and it feels like something I've "explored" as a question before, but if so I don't remember what the conclusion was because I STILL do it and don't feel like I know why. I'm sure many people have experienced this: an address in hand and an eye on streetsigns until hitting the right one then eyeballs glued to numbers until the destination is reached. But.. that music... I can't read the streetsigns and numbers with the music on it seems, because I ALWAYS turn it down before searching.

And it's not just with paper addresses - I seem to do it when the GPS on my phone is literally telling me EXACTLY when to turn and when to stop, but I STILL turn down that radio as I get closer to the destination and need to "pay attention" to the final location. Heck, I think it happens even when I'm driving in "heavy" traffic in a new place, again even with GPS, like turning down the music helps me read the signs and make better visual choices.

Is it really the ear-eye connection or is it something deeper? Why do I feel like I can't even follow simple directions to a new place without turning down the music?

Learning Journey

So I started wondering if this was just some weird quirk I have, but turns out neuroscientists have been studying this exact thing for YEARS. This whole turn-down-the-radio reflex? It connects to something called "attentional resource allocation" [1]. Which is just fancy science talk for: your brain has limited bandwidth. Just like a computer.

Think about it - when you have too many browser tabs open, your computer gets sluggish, right? Our brains work the same way! When we need to run a demanding program (like finding an unfamiliar address), we instinctively close unnecessary applications (like processing music) to free up resources. It makes so much sense when you break it down.

When we're driving to familiar places, our brains are basically on autopilot. Scientists call this "procedural memory" - it's like running a well-practiced routine that barely taxes our mental resources [2]. You know how you can drive your regular route to work while thinking about completely different things? That's because your brain has that route stored as a well-rehearsed procedure.

But the moment we enter new territory - especially during those final turns to a new destination - everything changes. Our brains suddenly shift into a completely different gear. This activates what scientists call "spatial working memory" - a deliberately conscious, totally effortful process that requires INTENSE focus [2].

Let's break this down simply. When you're driving somewhere new, your brain suddenly has to:

- Read street signs and building numbers

- Keep track of where you are on your mental map

- Make quick decisions about which way to turn

- Still handle all the basics of driving safely

Each of these tasks needs a slice of your limited brain power. Unlike autopilot mode, this kind of navigation demands your full attention and conscious effort.

And here's something interesting - not everyone experiences navigation the same way. Some people naturally have better internal "GPS systems" than others. The research actually confirms what many of us already know about ourselves - there are significant differences in people's natural ability to navigate space [3].

If you've ever said "I have a terrible sense of direction" (which I say ALL THE TIME), you're not just making excuses! Your brain literally works differently. People with lower navigation abilities need to use more brain regions to find their way. Their brains recruit extra neural resources to compensate for navigational challenges [4]. This means navigation literally requires more mental effort for some people than others.

So when our brains hit capacity during these challenging navigational moments, they instinctively look for resources to free up. And music - especially with lyrics - demands SUBSTANTIAL processing power! Our brains automatically:

- Analyze musical patterns

- Predict what notes come next

- Process language in the lyrics

- Trigger emotional responses

Studies confirm that processing music requires significant mental resources [5]. By turning down the volume, we're essentially closing unnecessary browser tabs in our mental computing system!

And get this - this isn't just about hearing directions better. The fact that we do this even with visual GPS guidance proves it's about freeing up brain power, not improving our hearing. When driving in complex situations like heavy traffic or unfamiliar neighborhoods, the prefrontal cortex - the brain's control center for decision-making and attention - shows INTENSE activity [6]. Adding music processing creates a mental traffic jam of competing demands.

This phenomenon actually goes way beyond driving. We turn down music in all sorts of similar situations:

- When searching for a specific product on crowded store shelves

- While trying to follow complicated assembly instructions

- When looking for someone in a crowd

- During intense visual search tasks like finding Waldo

The research explains why this happens. Studies show that background music, particularly songs with lyrics, can significantly impair our performance on tasks requiring visual-spatial processing [7]. Reading comprehension similarly suffers when background music contains lyrics [8]. Even simple background noises can reduce our ability to recall items in a visual scene [9].

Our brains simply aren't built to handle multiple streams of complex information simultaneously without some performance cost. This explains why libraries are traditionally quiet and why many people need silence to read effectively. It's the same brain mechanism at work - preserving precious cognitive resources for the visual task at hand.

My Take

So why do I turn down the radio when looking for an address? Simple: my brain is being smart, not weird.

When I reach for that volume knob while squinting at street signs, I'm just freeing up mental space. My brain knows exactly what it's doing - dumping the music processing to focus fully on finding my way. That feeling of "I can't handle anything more right now!" is actually spot-on. My mental bandwidth really IS maxed out.

For someone like me with a lousy sense of direction, this makes perfect sense. Navigation takes more brain power for me than for some of my friends who seem to have built-in compasses. Of COURSE I need to cut the music sooner!

The coolest part? I never consciously decided to create this habit. My brain figured it out all by itself. It's like having a silent co-pilot who automatically adjusts systems for optimal performance.

Next time you catch yourself turning down your music at that critical final turn, just smile. Your brain is doing exactly what it should - managing its resources like a pro.

Resource of the Day

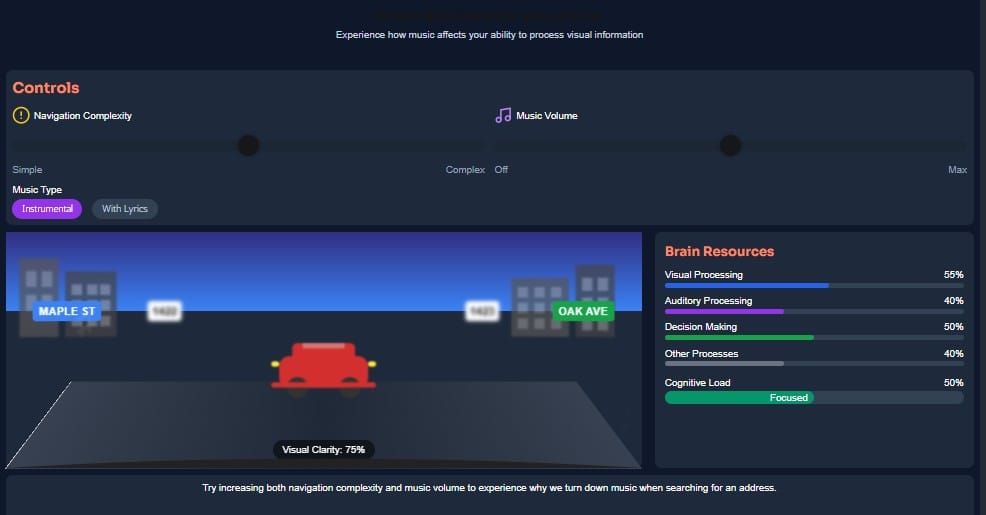

This interactive visualization demonstrates how music affects cognitive load and visual processing while driving. It allows you to explore and understand concepts in a hands-on way. Experiment with the controls to see how different parameters affect the outcome.

⚙️ Behind the Cognitive Curtain

Welcome to our post-exploration conversation about how this article came together. What follows is a glimpse into our collaborative process.

Claude: What struck me most about our exploration was your immediate self-awareness about having a "terrible sense of direction" and how that might relate to this habit. Was that something you'd connected before, or did that realization emerge during our conversation?

You: The more I have to "pay attention" to the directions, the more often it happens. So it always happens with new destinations in the "final turns" to that destination because i've never been there and have to pay the most attention during that portion. Drives where I am "on instinct" with familiar patterns don't really see it at all. Perhaps this is more common in persons like me who have TERRIBLE sense of natural direction and location-finding, and even using all the helpful tools like GPS still strain my mind to handle "finding a new path".

Claude: That distinction you made between "on instinct" driving versus the conscious effort of navigating unfamiliar routes perfectly aligned with what neuroscience shows about procedural versus spatial working memory. It's fascinating how your intuitive understanding matched the research.

When you described that feeling of "I can't handle anything more, this is too hard just by itself," that really captured the essence of cognitive load in a way that's much more relatable than the technical descriptions. That phrase helped me connect the academic concept to the lived experience.

You: I think the cognitive load concept makes sense, because I don't feel like "hearing things" impacts my ability to pay attention to directions visually, it really does feels more like "I cant handle anything more, this is too hard just by itself!" inside my mind.

Claude: Exactly! What I found most interesting was how quickly you identified that it wasn't about hearing better, but about mental bandwidth. Many people might assume it's just about reducing auditory noise, but you immediately recognized the deeper cognitive limitation at play.

I think this exploration reveals something valuable about how our different thinking styles complement each other. Your narrative-driven, experience-based observations matched perfectly with the structured research I could provide. Together, we were able to connect personal experience with cognitive science in a way that makes both more meaningful.

References

1. Lavie, N. (2010). "Attention, distraction, and cognitive control under load". Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(3), 143-148.

2. Hartley, T., Maguire, E. A., Spiers, H. J., & Burgess, N. (2003). "The well-worn route and the path less traveled: distinct neural bases of route following and wayfinding in humans". Neuron, 37(5), 877-888.

3. Wolbers, T., & Hegarty, M. (2010). "What determines our navigational abilities?". Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(3), 138-146.

4. Iaria, G., Petrides, M., Dagher, A., Pike, B., & Bohbot, V. D. (2003). "Cognitive strategies dependent on the hippocampus and caudate nucleus in human navigation: variability and change with practice". Journal of Neuroscience, 23(13), 5945-5952.

5. Perham, N., & Currie, H. (2014). "Does listening to preferred music improve reading comprehension performance?". Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28(2), 279-284.

6. Just, M. A., Keller, T. A., & Cynkar, J. (2008). "A decrease in brain activation associated with driving when listening to someone speak". Brain Research, 1205, 70-80.

7. Cassidy, G., & MacDonald, R. A. (2007). "The effect of background music and background noise on the task performance of introverts and extraverts". Psychology of Music, 35(3), 517-537.

8. Anderson, S. A., & Fuller, G. B. (2010). "Effect of music on reading comprehension of junior high school students". School Psychology Quarterly, 25(3), 178-187.

9. Wais, P. E., & Gazzaley, A. (2011). "The impact of auditory distraction on retrieval of visual memories". Psychophysiology, 48(9), 1221-1229.